What If Buddhists Designed Apps

Abstract

This paper examines two self-tracking apps inspired by Buddhist ideas and practices but designed for the broader public: Mitra: Track What Matters Most and Stop, Breathe & Think. It shows how the apps enable users to develop greater emotional and ethical awareness, and it argues that their minimalist and customizable design features help mitigate against users becoming dependent on the technology itself. It then illustrates ways that other apps like Calm instead seek to lure users into their technology and keep them there. It concludes with a discussion of how such hooks and attention-economic strategies strengthen habits of consumption.

Introduction

Self-tracking mobile applications (apps) enable people to record, analyze, and reflect on data about themselves, such as their steps, heart rate, diet, screen activity, and sleep. Digital technology allows for more frequent and extensive self-monitoring than previous diaries and logs, and people are increasingly turning to wearable devices such as smart watches and fitness trackers to engage in quantified self-tracking (Vogels 2020). These technologies create "a laboratory of the self" that amplifies certain aspects of oneself while reducing and restricting others (Kristensen and Ruckenstein 2018, 3625–26), with people predominantly tracking their physical activity, food, and weight (Neff and Nafus 2016, 23). According to Gina Neff and Dawn Nafus (2016), the five common purposes for self-tracking are (1) to evaluate and monitor progress toward a certain "target or goal" (70–71); (2) to "elicit sensations" by "observing physical signals felt in the body and … recordings of them" (75); (3) to satisfy "aesthetic curiosity" by noticing "what is [normally] overlooked" (80–81); (4) to "debug" by recording symptoms, their possible "triggers or causes," as well as possible solutions (84–85); and (5) to cultivate a habit by changing the triggers that "create a propensity to do or avoid doing something" (89). Their critique of many off-the-shelf tracking options is that, while they claim to empower people, they do not actually help people figure out which questions they should be asking, much less how to test ideas or make discoveries (11).

If one considers the question "What would the Buddha track?" and reflects on the five purposes of self-tracking, one can easily see how one might use self-tracking apps to evaluate and monitor meditation progress, to observe the four foundations of mindfulness, to encourage right view and right thought, to appreciate the four noble truths, or to cultivate ethics, concentration, and wisdom. Searching among the two million apps available in the Apple Store and on Google Play (Clement 2019), one finds more than five hundred apps for "Buddhism"—some associated with particular traditions of Theravada (Access to Insight), Mahayana (SGI-USA), or Vajrayana (the Dalai Lama) Buddhism, and others encompassing a variety of traditions. The vast majority are mindfulness apps created by non-Buddhists, although there are some meditation apps created by Buddhists, such as Rohan Gunatillake's Buddhify and Matthieu Ricard's Imagine Clarity (Littlefair 2017). Some scholars argue that such apps convey "digital dharma"—a digitized form of the Buddha's teachings (Grieve 2017a, 6; Veidlinger 2015, 14)—while others criticize the consumption of Buddhist teachings and practices on phones, tablets, and other mobile devices for promoting an individualistic approach to Buddhism as well as attachment to the self, as people collect apps supporting their beliefs, habits, and preferences, which become representations of their values and identities (Wagner and Accardo 2015, 102).

This paper examines two self-tracking apps inspired by Buddhist ideas and practices, but designed for the broader public: Mitra: Track What Matters Most and Stop, Breathe & Think. Although scholars have shown how digital devices can adversely affect emotional development, resulting in an inability to identify the feelings of others or themselves, a loss of empathy, and a diminished capacity for self-reflection (Turkle 2015), these apps seek to increase emotional awareness. The Mitra app, designed and developed by the Dalai Lama Center for Ethics and Transformative Values at MIT in partnership with Hope Lab ( https://hopelab.org/ ), was inspired by Buddhist notions of a "virtuous friend" (Sanskrit kalyāṇa-mitra). By helping users identify their core values, cultivate emotional awareness, and align their emotions with their values, they hope that users can "positively transform the mind" so that it becomes "a better friend and ally." 2 Users record their day, tracking the extent to which they lived their values and the intensity of emotions they felt in the day; they then evaluate and reflect on their ethical and emotional life after viewing graphs and statistics about their baseline and average values and emotions. Users report feeling more self-aware after they track their emotions and values regularly. Stop, Breathe & Think is a comparable app developed by Tools for Peace (http://www.toolsforpeace.org), a non-profit organization founded in 2000 by Venerable Lama Chödak Gyatso Nubpa that seeks to strengthen social and emotional learning by providing practical methods for developing compassion, peace, and well-being.

Unlike other apps designed to foster dependency on the technology itself, these apps facilitate greater emotional and ethical awareness for their users. Howard Gardner and Katie Davis use the terms "app-dependent" and "app-enabling" to distinguish between the way apps can either restrict and determine user procedures, or become springboards to new experiences, areas of knowledge, and meaningful relationships (2014, 9–10). As we will see, apps like Calm use design features to encourage app-dependence, while apps like Mitra eschew them. Checking apps on one's mobile phone can be addictive: studies show the average US user spends over five hours a day on their mobile device (Khalaf and Kesiraju 2017) and checks their phone between 30 and 150 times per day; 79% check their device within fifteen minutes of waking up in the morning (Eyal 2014, 1). Message notifications and red dots hovering over apps lure people in, and they find themselves still scrolling through feeds an hour later (Eyal 2014, 7–10); the pull-to-refresh mechanism, where one swipes down to see content below, has been compared with a slot machine (Lewis 2017). In fact, several designers and engineers who helped create such technology have become disaffected by such addictive feedback loops and the harvesting of user preference data that could be sold to advertisers in the internet "attention economy." This addictive cycle resembles the Buddhist chain of dependent origination that describes the process through which one's craving turns into clinging and ultimately suffering. Satisfying desires instantaneously with the touch of a screen can prevent one from discerning the role of craving in perpetuating suffering, which Diane Winston calls the "cyber-catch." She writes, "What happens when reflection time is inhibited? Part of breaking the chain depends on our having some space for reflection. What happens when we throw the speed of the Internet into this equation? .… We are losing the space between the desire and the satisfaction of desire" (2002, 6). Digital devices can fuel cravings that Buddhists seek to dissipate.

Emotions are powerful triggers that establish and maintain our digital habits. As Nir Eyal explains, "Emotions, particularly negative ones, are powerful internal triggers and greatly influence our daily routines. Feelings of boredom, loneliness, frustration, confusion, and indecisiveness often instigate a slight pain or irritation and prompt an almost instantaneous and often mindless action to quell the negative sensation" (Eyal 2014, 48). When apps alleviate such negative feelings, people form strong positive associations with them and habituate themselves to use them when they experience such negative internal triggers. However, many Buddhist traditions encourage training of the mind as an antidote to such vulnerability to emotional triggers (Goleman 2003, 3). As Matthieu Ricard observes, "obscuring emotions impair one's freedom by chaining thoughts in a way that compels us to think, speak, and act in a biased way. By contrast, constructive emotions go with a more correct appreciation of the nature of what one is perceiving—they are grounded on sound reasoning" (quoted in Goleman 2003, 76). Emotions arise because of circumstances, habits, and tendencies; one can work with emotions themselves by using antidotes to neutralize the emotion (such as contemplating unpleasant aspects of an object that one craves), by meditating on their empty nature, or by transforming them and using them as catalysts for liberation (Goleman 2003, 82). The timing of such practices can occur after emotions arise, as they arise, or before they arise, in the case of advanced practitioners for whom emotions do not have such a compelling power (Goleman 2003, 83–84).

This article shows how Mitra and Stop, Breathe & Think facilitate emotional and ethical awareness, and it argues that their minimalist and customizable design features mitigate against "app-dependence." It then illustrates ways that other apps like Calm instead seek to lure users into their technology and keep them there. It concludes with a discussion of how such hooks and attention-economic strategies strengthen habits of consumption.

Minimalist and Customizable Features of Mitra

Mitra allows users to observe, analyze, and evaluate their emotions and values, and its minimalist and customizable features mitigate against users becoming dependent or constrained by the app. Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi, the director of the Dalai Lama Center for Ethics and Transformative Values at MIT, said that the app developers paid special attention to the intention and framing of the Mitra app: unlike many apps that fuel addiction in their design by encouraging users to constantly return to them, they designed Mitra to be opened once or twice a day (telephone interview by author, August 18, 2019). Mitra begins by asking users to identify eight deeply held values and emotions, to select three of each to track, and to each day record—on a scale of 0 to 10—the intensity of their values and felt emotions throughout the day. After logging their scores, a prompt asks them to journal personal reflections while it displays their daily scores.

Venerable Tenzin described the tracking as a sort of Buddhist practice in which one first becomes mindful of the values that drive one's thinking and decision making, and then draws awareness to emotional states. Specifically, he said it derived from Abhidharma literature about mindfulness of emotional states, where people learn how to (1) observe their emotional state, (2) analyze exactly what it is (through labeling, naming, etc.), and (3) evaluate for themselves whether the state is positive, negative, or neutral. Once one names the state and understands its intensity and the frequency with which it happens in day-to-day patterns, then one can engage in further analysis of when it arises and what its trigger mechanisms are (Priyadarshi, telephone interview by author, August 18, 2019). Mitra has users select emotions based on their desirability—whether, for example, upon waking up one would desire to be in that emotional state—and then track their emotions longitudinally, helping them think through how dominant those emotional states are day-to-day. Through this process, users can discover which are the dominant emotional states or values priming their decisions; they become clearer about what drives their decision-making, which is oftentimes buried deep under the narratives.

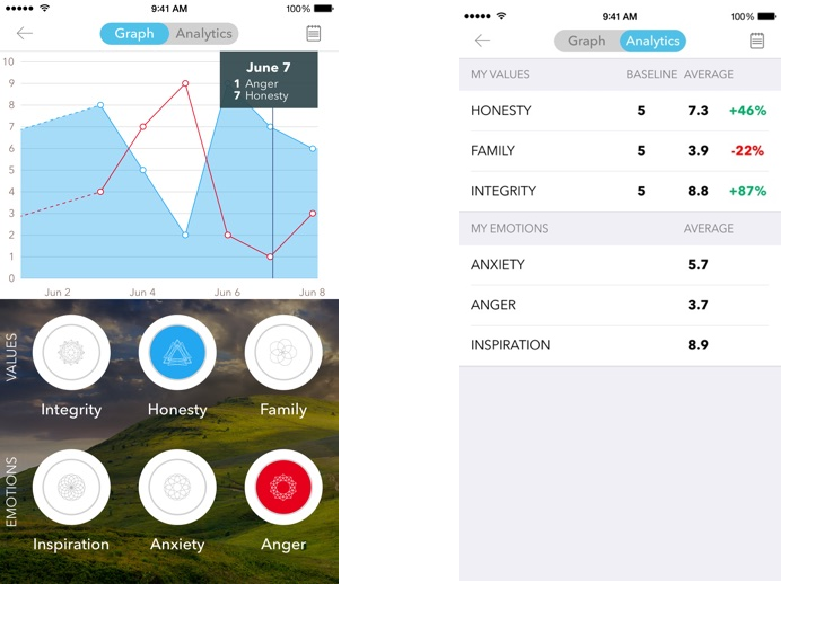

With regard to values, Venerable Tenzin remarked that people aren't generally aware of their drivers: "We make decisions—many are habitual. Rarely do we know what is really priming our decisions" (Priyadarshi, telephone interview by author, August 18, 2019). Through analysis you can recognize, for example, that even though you may say you want to help the world, if you do not receive recognition or acknowledgment for your actions, your emotional state is lower. The app graphs emotions and values over a period of time, showing interesting correlations between your emotional states and the values driving you (fig. 1). The presumption—and preliminary finding—is that when your core values are honored in your life, you will experience more of these joyful emotions; when those values are getting challenged, or you are not in alignment with them, then your emotional state will reflect that.

Figure 1.

Mitra's graph and analytics of trends in values and emotions data

The app is minimalist by design: visually, the creators wanted the app to be clean and to-the-point, and philosophically, they wanted to avoid dictating which values or emotions users should track by instead allowing users to determine what to track (Priyadarshi, telephone interview by author, August 18, 2019). They also allow users to decide if and when they would like to be prompted to do the tracking. These customizable features make the app more self-driven than other-determined; it becomes a tool for self-discovery rather than self-improvement. Optimization exemplifies our biomedicalized culture, which encourages people to measure themselves in the context of others, with those falling outside the norm deemed in need of medical intervention or self-discipline (Neff and Nafus 2016, 38–39). In such circumstances, as Neff and Nafus note, "A device user may come to see himself instead, through the data and the systems designed to encourage behavior change, as a person who failed. In this situation, the technology acts as a kind of surveillance substitute" (Neff and Nafus 2016, 41–42). Self-tracking apps tend to maintain this cultural script, but Mitra changes the script by making different "givens"—allowing users to determine and define what they are tracking. As Neff and Nafus remark, "Change the givens, and you change the conversation" (2016, 47).

The first and foremost ethical consideration in the development of Mitra was privacy. Although the app collects data about how many are exploring trust, envy, sadness, and other emotions, it maintains privacy by not monitoring its users. The developers also decided against enabling sharing of emotional states to encourage greater data privacy (Priyadarshi, telephone interview by author, August 18, 2019). This addresses some fundamental concerns about self-tracking apps, articulated by Neff and Nafus: "Digital traces of our every move can lay the groundwork for terrible social consequences, such as rampant privacy violations, the commodification of daily living, 'healthism' (the fetishization of anything and everything deemed healthy), and a preoccupation with the personal that erodes our capacity for coordinated community action" (2016, 7). Although some reviewers of Mitra view the inability to share results with others or lack of built-in explanation of the content (for example, definitions of emotions or interpretations of graphs) as a drawback to the app ("Ericka D." 2017), these limitations seek to safeguard privacy and allow users greater self-determination.

Extensive User Choice in Stop, Breathe & Think

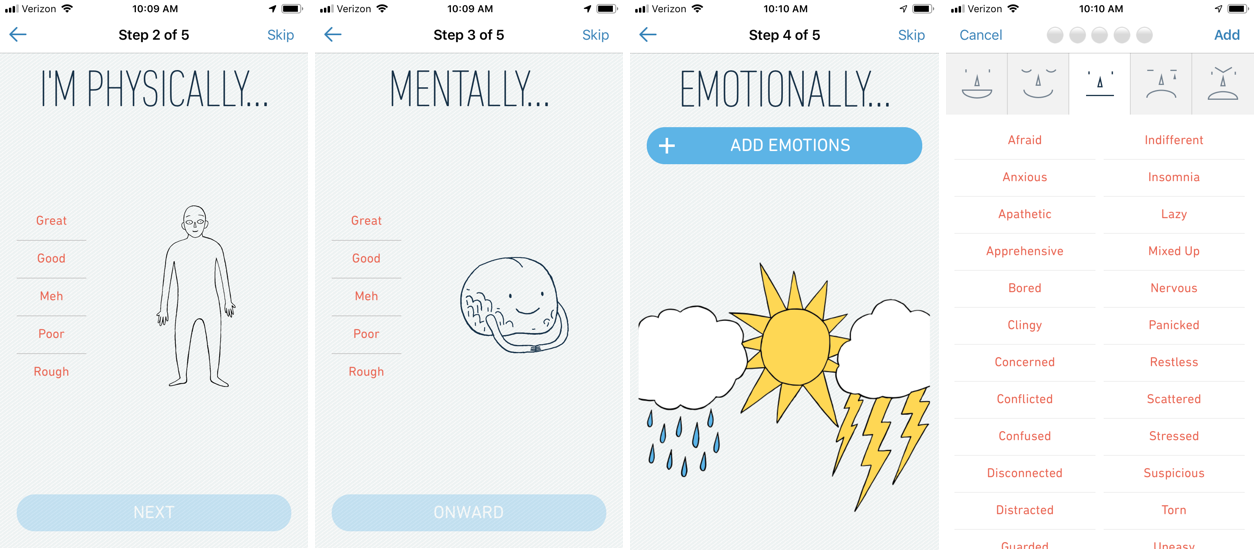

Stop, Breathe & Think also uses minimalist design features, but it offers an extensive list of pleasant, neutral, and unpleasant emotions for users to choose from. It starts with a simple "How are you?" check-in, where users report how they are physically and mentally—on a scale of great/good/meh/poor/rough—and then emotionally through drop-down menus associated with happy, content, anxious, sad, and angry states (fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Reporting physical, mental, and emotional states

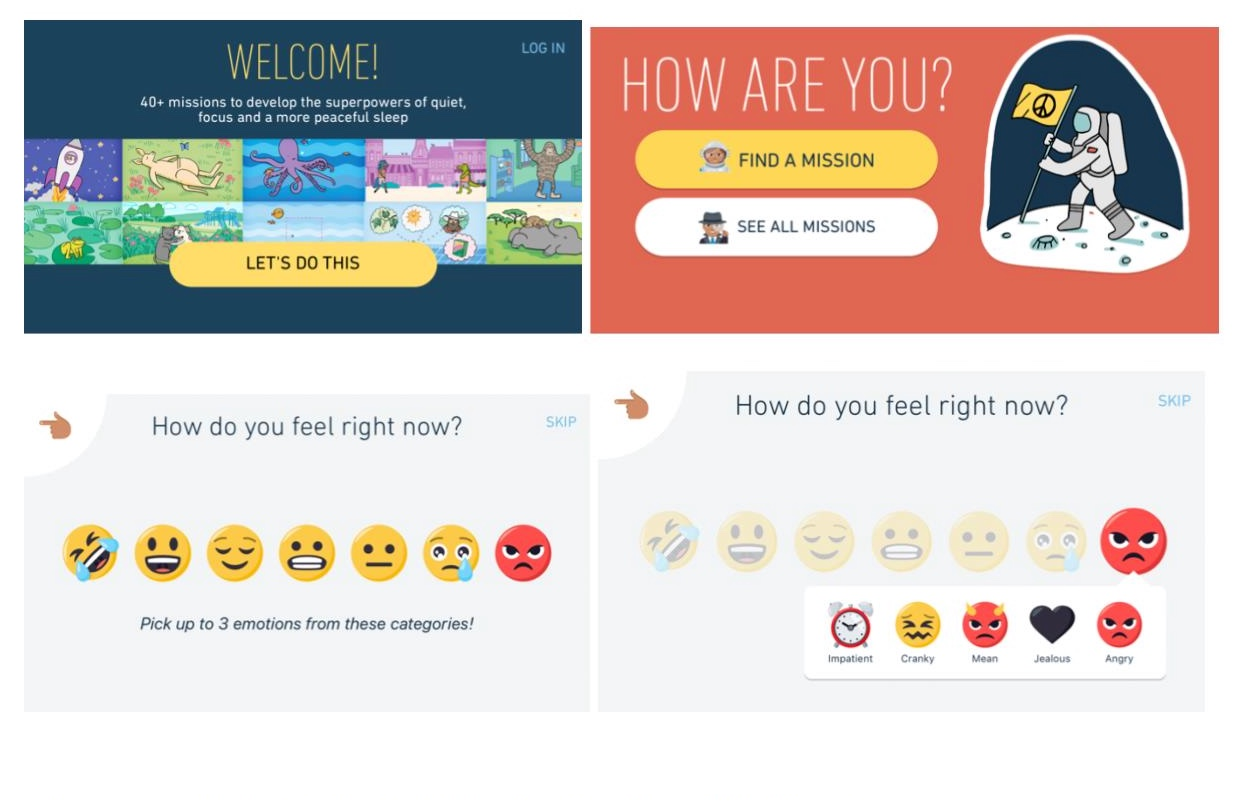

After the user reports their physical, mental, and emotional states, the app recommends specific meditations based on those particular circumstances. For example, if one is feeling anxious or panicked, the app recommends a self-forgiveness meditation and a grounding mindfulness practice. Originally designed for teens and adults, Stop, Breathe & Think is also available in a version for children that encourages the development of mindfulness and emotional literacy for children ages 5–10. Developed in partnership with Susan Kaiser Greenland, author of Mindful Games, the app for kids includes game design elements, describing over forty different "missions" in categories that include "quiet," "focus," "caring & connecting," "energizing," "meltdown," "open mind," "sleep," and "bedtime stories." After children (or their parents) click on "find a mission," it then asks them how they are feeling and shows different categories, from super-excited to angry, with emoji faces (fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Missions and emotions in Stop, Breathe & Think for Kids

After one identifies the emotion, a rocket appears on the lower right of the screen to "launch" the mission, which is an animated video designed to promote care and connection if one feels angry, or quiet if one feels agitated. The videos often encourage the children to move and home in on their sensory experience while they are connecting with and processing their emotions.

Like Mitra, Stop, Breathe & Think explicitly grounds itself in mindfulness practices and seeks to cultivate emotional awareness and reflection, although it has a younger target demographic. Both apps connect mindfulness with ethical development, the former through its focus on identifying core values and aligning values with emotions, and the latter with its goal of developing kindness, compassion, and self-compassion. Both apps are free, though Stop, Breathe & Think does have a subscription service that gives access to more mindfulness activities and "missions." It shares ten percent of its net revenue with Tools for Peace for its school programs for at-risk youth. This attention to ethics and free distribution through nonprofit organizations (the Center for Ethics at MIT and Tools for Peace, respectively) set Mitra and Stop, Breathe & Think apart from other subscription-based mindfulness apps. These Buddhist-inspired apps draw awareness to emotions and values to reveal habitual patterns of emotionally and ethically acting in the world.

Enticing and Entangling User Attention in Calm

By contrast, other apps like Calm use addictive feedback loops to lure users into an app and keep them there. Venerable Tenzin drew a distinction between Mitra and apps like Calm and Headspace that serve as an on-ramp to meditation. He noted how people can become addicted to such apps, only staying calm when looking at the screen, and how the app industry's success is based on an addiction algorithm. Drawing an analogy with the Buddha's parable of the raft, he said that a mindfulness meditation app is an oxymoron. Whereas the Buddha encouraged people to discard the raft once they had crossed the shore, apps promote the opposite: "You're carrying it on your back all the time" (Priyadarshi, telephone interview by author, August 18, 2019).

Calm, named the "Best of 2018 Award Winner" by Apple, was valued at $1 billion in February of 2019, was estimated to have more than forty million downloads worldwide and over one million paying subscribers, and was the top grossing health and fitness app and twentieth overall on iOS (LaVito 2019). Headspace, its competitor in the meditation app market, is the seventh-highest-grossing health and fitness app, valued at $320 million and generating more than $100 million in revenue every year (LaVito 2019). Fighting to dominate a $1.2 billion meditation market, Michael Acton Smith, the co-CEO and co-founder of Calm, notes that Headspace has six times as many employees as Calm (230 to 240) (Potkewitz 2018), while Rich Pierson, the CEO and cofounder of Headspace, points to its cofounder Andy Puddicombe's ten years studying meditation at Buddhist monasteries as a sign of Headspace's authenticity, compared to the Calm cofounders' background in online gaming and advertising (Potkewitz 2018). Headspace, founded in 2010, had led the meditation category until Calm won the iPhone App of the Year award in December 2017. Headspace uses cartoons narrated by Mr. Puddicombe to walk users through meditation sessions, offering sessions for stress, sleep, productivity, and fitness; Calm offers different meditation teachers, nature scenes, music playlists, and sleep stories narrated by actors such as Matthew McConaughey and Stephen Fry—in fact, they estimate that half of their users use it as a sleeping aid (Potkewitz 2018), and they plan to incorporate more celebrity content tie-ins in the future (Constine 2019). Headspace has partnered with the NBA as well as eleven airlines including Delta and United, and Calm has partnered with American Airlines, so that their soothing nature videos will play on all seat-back screens to an estimated 200 million passengers a year (Potkewitz 2018).

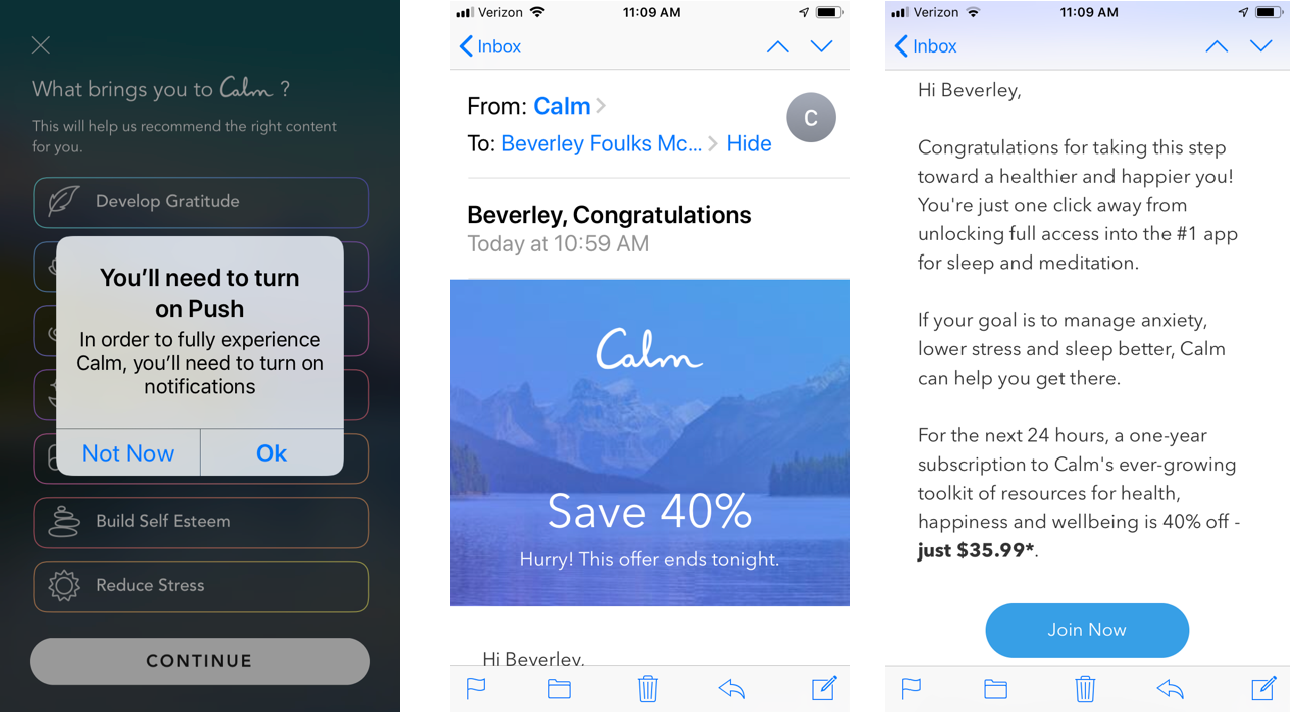

Calm's default setting of a lake with mountains in the background and sounds of nature, with birds chirping and rivers flowing, evokes a sense of calm, and you can adjust the visuals and sounds to wood in the fireplace, evening crickets, rain on leaves, and more (Graham 2017). Yet as Venerable Tenzin notes, the app design seeks to draw the user's attention toward the screen rather than directing it toward their present bodily, mental, or emotional experience. For example, in a guided meditation session, a gentle voice might prompt you to breathe deeply and clear your mind, while you hear default ambient sounds playing in the background (Fagan 2018). This promotes app-dependence, which Howard Gardner and Katie Davis say is "when technology is used as a starting point, endpoint, and everything in between—in other words, when individuals look to their apps and devices first before looking inside themselves or reaching out to a friend" (2014, xiii). The sleek visuals and ambient sounds of Calm draw the user's attention toward the screen rather than making them more mindful of their own embodied experience (fig. 4). As Kathryn Lofton has observed, "Commercial products don't want to disturb their consumers with anything that upsets the shushing lull of their cloaked commerce" (2017, x). Calm exemplifies this through ambient sounds and high-quality images designed to keep the user immersed in the app and seduce them into unlocking music and stories beyond their reach.

Figure 4.

Sleep, Meditate, and Music tabs in Calm

Sleep stories rely on the actors' soothing voices to lull users to sleep, calming meditations rely on images and sounds to evoke calm, and music playlists suggest one need only listen to achieve a flow state or fall asleep. However, glowing brightest of all, for those who downloaded the free app, is the purple button inviting users to "Unlock Calm Premium" (fig. 4). Indeed, if one observes carefully, one sees most content is locked and kept exclusively for those who subscribe to Calm. Users can try one sleep story, or use the app for seven days of meditation, but otherwise most of the sleep stories, meditations, and all of the music are unavailable. Calm employs a variety of external triggers to hook the user, including a notification right at the outset that one needs to allow notifications to "fully experience Calm," and an email sent within twenty minutes that urges one to "hurry" to take advantage of a twenty-four-hour offer to get a yearly subscription for only $36—forty percent off the regular yearly subscription price (fig. 5). Such alerts seek to externally trigger certain actions that will eventually become habits. Once the user associates the app with calm and sleep, they themselves will trigger the cycle. As Nir Eyal notes, "By cycling though successive hooks, users begin to form associations with internal triggers, which attach to existing behaviors and emotions. When users start to automatically cue their next behavior, the new habit becomes part of their everyday routine" (2014, 7).

Figure 5.

External triggers by Calm

Calm exemplifies the marketing and commodification of mindfulness that has been criticized as McMindfulness by Ron Purser, David Loy, and others (Purser 2019, Forbes 2019, Hyland 2017, Purser and Loy 2013). Purser writes of McMindfulness, "Although derived from Buddhism, it's been stripped of the teachings on ethics that accompanied it, as well as the liberating aim of dissolving attachment to a false sense of self while enacting compassion for all other beings" (2019, 8). Mindfulness is sold and marketed as a vehicle for self-improvement or self-optimization instead of liberation for all sentient beings. As Ann Gleig observes in American Dharma, such sociocultural critiques of mindfulness have prompted four main Buddhist responses—first, that it serves as upaya or skillful means; second, that Buddhism has always emphasized pragmatic benefits and been embedded in unjust sociocultural and economic systems; third, that it nevertheless reduces individual suffering and can positively affect institutions; and fourth, that it uncouples a universal awakening from Buddhism (2019, 64–65). Calm and Headspace have certainly reached a wide audience, skillfully introducing many people to meditation and bringing therapeutic benefit. However, in contrast with Mitra and Stop, Breathe & Think, they not only overlook ethics, but actively employ techniques such as external triggers and celebrity endorsements to entice users into their apps.

As we have seen, some mindfulness apps seek to lure users in and make them dependent on the app itself. As Shannon Vallor notes, "New media advertising techniques fueled by the power of 'Big Data' subject us to a constant flow of solicitations custom-tailored to inflame our desire, to strengthen our existing consumption habits and expand them to new types of goods, and to convince us that our wants and needs are one and the same" (Vallor 2016, 123). David Loy has argued that in the United States, our (corporate) media institutionalize delusion, because their primary focus is profiting from advertising and consumerism, rather than informing us about the crucial issues of our day. He suggests that delusion functions as one of the three poisons alongside our present economic system, which can be understood as institutionalized greed, and our militarism, which institutionalizes aggression (Loy 2016; 2008).

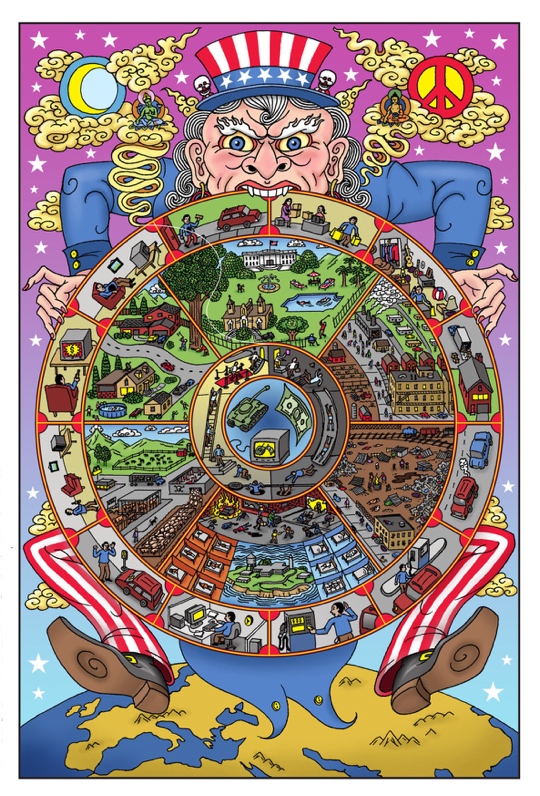

Figure 6.

Americosmos (Drda 2012)

The artist Darrin Drda depicts this process in his cartoon "Americosmos" (fig. 6), which shows how capitalism creates hungry selves who, feeling insecure and unsatisfied, purchase commodities to try to fix their unhappiness. The three poisons of greed, hatred, and delusion are depicted by a dollar bill, tank, and television representing materialism, militarism, and the media. The ring of financial karma depicts people climbing the ladder of prosperity and sliding into debt. The six realms of existence show the heavens of ultra-wealthy arrogantly living in mansions and riding in limousines; the wealthy enviously living in suburban homes with expensive cars; the working class living in modest homes, apartments, and trailers; the animals confined and subject to cruelty; the homeless who wander in search of food and shelter; and the disenfranchised and incarcerated—people locked in prisons, mental institutions, or army barracks. The twelve steps of codependent consumerism begin with shopping, which leads to the accumulation of material objects, which require storing and lead to the purchase of a house, which necessitates having a vehicle to transport one's possessions, which requires that one buy gas, which contributes to debt and the need for employment, which generates stress, which prompts the desire for relaxation and TV watching, whose advertising promotes a sense of lack or emptiness, which promotes the impulse to shop.

Conclusion

Having used these apps, I can attest to the appeal of sleek visuals and soothing impact of ambient sounds in Calm, and I can vouch that maintaining a daily log of emotions and values requires much greater self-discipline. In my research study of college students who used Mitra and Stop, Breathe & Think, they reported increased introspection and daily reflection after using the apps, but they also felt a lack of engagement or stimulation by them, and they said the tracking felt superficial since it did not address why they had such emotions or values. However, many students said Mitra influenced their behavior: for example, those who identified family as a value found themselves calling and connecting with their parents more frequently.

In his examination of Buddhify, Greg Grieve argues that its user interface cultivates an experience of mindfulness not only through its content and images but also through ritualization—the step-by-step process of navigating through screen menus and commands. He writes, "The app features liminal bubbles of spirituality, micro third spaces outside of work and home in which users are temporarily removed from everyday time and space and return renewed in spirit" (2017b, 203). Calm also provides such liminal bubbles with its high-resolution images, ambient sounds, and soothing storytellers, but it does not empower users as much as make them reliant on technology to become calm. Instead of fostering deeper awareness of one's physical, mental, and emotional state, it employs every means at its disposal to induce relaxing and somniferous states. Whereas Mitra and Stop, Breathe & Think seek to improve users' emotional literacy, reflective capacity, and ethical compass so that users might use their apps as a springboard to act more compassionately and ethically in the world, commercial products such as Calm try to lure users back to their app as an oasis of tranquility. Although one could argue that it might serve as a type of training wheel for meditation, it offers little indication that it ever wants those training wheels taken off.

Acknowledgments

Support for this article was provided by Public Theologies of Technology and Presence (http://www.shin-ibs.edu/luce/) , a journalism and research initiative based at the Institute of Buddhist Studies and funded by the Henry Luce Foundation.

Footnotes

FAQs, Mitra, v. 1.2 (Dalai Lama Center for Ethics and Transformative Values, 2018).

References

- Clement, J . 2019. " Number of Apps Available in Leading App Stores as of 2nd Quarter 2019." Statista. Accessed August 10, 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/.

- Constine, Josh . 2019. " Calm Raises $27M to McConaughey You to Sleep." TechCrunch . July 1, 2019. https://techcrunch.com/2019/07/01/calm-sleep-stories/.

- Drda, Darrin . 2012. " Americosmos: A Mandala of the Unenlightened States of Affliction." Reality Sandwich. February 26, 2012. https://realitysandwich.com/138610/americosmos_mandala_unenlightened_states_affliction/.

- " Ericka D ." 2017. Review of "Mitra". Common Sense Education. Updated February 2017. https://www.commonsense.org/education/app/mitra-track-what-matters-most.

- Eyal, Nir . 2014. Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products. New York: Penguin.

- Fagan, Kaylee . 2018. " How to Use Calm, the Apple Award-winning Meditation App That's Now Valued at $250 Million." Business Insider . March 27, 2018. https://www.businessinsider.com/calm-meditation-app-cost-pictures-valuation-2018-3.

- Forbes, David . 2019. Mindfulness and Its Discontents: Education, Self, and Social Transformation . Halifax, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing.

- Gardner, Howard , and Katie Davis . 2014. The App Generation: How Today's Youth Navigate Identity, Intimacy, and Imagination in a Digital World . New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Goleman, Daniel . 2003. Destructive Emotions: How Can We Overcome Them? A Scientific Dialogue with the Dalai Lama . New York: Bantam Books.

- Gleig, Ann . 2019. American Dharma: Buddhism Beyond Modernity. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Graham, Jefferson . 2017. " Apple's Favorite App of the Year Wants You to Unplug." USA Today . December 7, 2017. https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/talkingtech/2017/12/07/apples-favorite-app-year-calm-wants-you-unplug/929644001/.

- Grieve, Gregory Price . 2017a. Cyber Zen: Imagining Authentic Buddhist Identity, Community and Practices in the Virtual World of Second Life. New York: Routledge.

- Grieve, Gregory Price . 2017b. " Meditation on the Go: Buddhist Smartphone Apps as Video Game Play." In Religion and Popular Culture in America, 3rd ed., edited by Bruce David Forbes and Jeffrey H. Mahan, 195–213. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hyland, Terry . 2017. " McDonaldizing Spirituality: Mindfulness, Education, and Consumerism." Journal of Transformative Education 15 (4): 334–56. doi: 10.1177/1541344617696972.

- Khalaf, Simon , and Lali Kesiraju . 2017. " U.S. Consumers Time-Spent on Mobile Crosses 5 Hours a Day." Flurry Analytics (blog) . March 2, 2017. http://flurrymobile.tumblr.com/post/157921590345/us-consumers-time-spent-on-mobile-crosses-5.

- Kristensen, Dorthe Brogård, and Minna Ruckenstein . 2018. " Co-evolving with Self-tracking Technologies." New Media & Society 20 (10): 3624–40. doi: 10.1177/1461444818755650.

- LaVito, Angelica . 2019. " Relaxing App Calm Raises $88 Million, Valuing It $1 Billion." CNBC.com . February 6, 2019. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/02/05/calm-raises-88-million-valuing-the-meditation-app-at-1-billion.html.

- Lewis, Paul . 2017. " 'Our Minds Can Be Hijacked': The Tech Insiders Who Fear a Smartphone Dystopia." Guardian , October 6, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/oct/05/smartphone-addiction-silicon-valley-dystopia.

- Littlefair, Sam . 2017. " 15 Buddhist Apps to Help Recognize You Don't Really Need a Buddhist iPhone App." Lion's Roar: Buddhist Wisdom for Our Time . June 23, 2017. https://www.lionsroar.com/buddhist-iphone-apps/.

- Lofton, Kathryn . 2017. Consuming Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Loy , David R . 2008. Money, Sex, War, Karma: Notes for a Buddhist Revolution. Boston: Wisdom Publications.

- Loy , David R. 2016. " The Challenge of Mindful Engagement." In Handbook of Mindfulness: Culture, Context and Social Engagement , edited by Ronald E. Purser, David Forbes, and Adam Burke, 15–26. Switzerland: Springer.

- Neff, Gina , and Dawn Nafus . 2016. Self-Tracking. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Potkewitz, Hilary . 2018. " Headspace vs. Calm: The Meditation Battle That's Anything but Zen." Wall Street Journal, December 15, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/headspace-vs-calm-the-meditation-battle-thats-anything-but-zen-11544889606.

- Purser, Ronald . 2019. McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality. London: Repeater.

- Purser, Ronald , and David Loy . 2013. " Beyond McMindfulness." Huffpost , July 1, 2013, updated August 31, 2013. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/beyond-mcmindfulness_b_3519289.

- Turkle, Sherry . 2015. Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age . New York: Penguin.

- Vallor, Shannon . 2016. Technology and the Virtues: A Philosophical Guide to a Future Worth Wanting . New York: Oxford.

- Veidlinger, Daniel . 2015. "Introduction." In Buddhism, the Internet, and Digital Media: The Pixel in the Lotus, edited by Gregory P. Grieve and Daniel Veidlinger, 1–20. New York: Routledge.

- Vogels , Emily A. 2020. " About One-in-Five Americans Use a Smart Watch or Fitness Tracker." Pew Research Center. January 9, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/01/09/about-one-in-five-americans-use-a-smart-watch-or-fitness-tracker/.

- Wagner, Rachel , and Christopher Accardo . 2015. " Buddhist Apps: Skillful Means or Dharma Dilution?" In Buddhism, the Internet, and Digital Media: The Pixel in the Lotus, edited by Gregory P. Grieve and Daniel Veidlinger, 134–52. New York: Routledge.

- Winston, Diana . 2002. " Filling Our Heads and Instant Fulfillment: A Buddhist Muses on the Internet. " ReVision 24 (4): 4–6.

What If Buddhists Designed Apps

Source: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jjadh/5/2/5_3/_html/-char/en

Posted by: restercoorms.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What If Buddhists Designed Apps"

Post a Comment